|

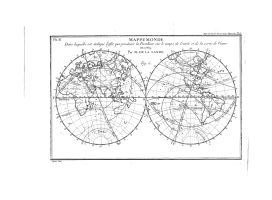

Written on Venus's transit of 1769 Preparation of the transit observations of 1769Observations of 1769Preparation of the transit observations of 1769Anonymous, HMARS 1757 p. 99-108 (History part) [[ HMARS-1757 p.99-108 ]] This text is a summary of the report from Lalande (p. 232-253) on predictions for 1769. Lalande 1757, HMARS 1757 p. 232-250 [[ HMARS-1757 p.232-253 ]] Joseph-Jérôme de Lalande (1732-1807) got deeply involved in the prediction of the transits of 1761 and 1769. In 1757, he published a Mémoire sur les passages de Vénus (Report about Venus transits), in which he explains a graphical method to determine the parallax effect during Venus’ transit. He assumes a value of the solar parallax of 10" (page 234). Next, he draws a map (page 239) and indicates the values of the parallax with the help of different arcs that permit a direct reading without calculations. For the 1769 transit, Lalande (page 244) predicted that the largest parallax differences should occur at (Saint) Petersburg and Mexico City. He summarizes (page 245) a few geometrical properties about the stereographic projection : a circle on the sphere will be transformed in a circle on the plane. Then (page 249), he connects the parallax to the Earth mass through the “knowledge of [gravitational] attraction” (it should be noted that, p. 249, the word "increases" should be replaced by "decreases"). This map titled "Mappemonde" (world map) was published in the Science Academy Reports of 1757. This map represents the visibility zones of the 1769 transit in Europe, America and then Asia. Lalande

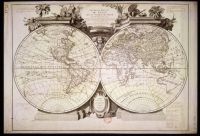

1760, Venus figure 1769 Joseph-Jérôme de Lalande (1732-1807) published in 1760 a world map that represents the visibility zones of the 1769 Venus transit in northern Europe, in America, in the Pacific Ocean and then in Asia. Lalande titled it "Figure du passage de Vénus" (Venus transit figure). This map is an improved version of the one included in the Royal Science Academy Reports of 1757 (fig. 6 p. 253). Lalande 1764, figure of the transit [[ 20269-6 (001à026) ]]

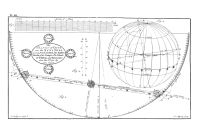

Ferguson 1763, Ph.tr. 53, p. 30 [[ Ph.tr.-53 p.30-et schémas]] James Ferguson (1710-1776) published his predictions on the 1769 Venus transit in 1763. He wrote that this transit will be “better” for the solar parallax determination than the one of 1761. However, minimum distances of the centers of the Venus and Sun’s discs will be slightly larger in 1769 than in 1761 (10.2' instead of 9.5'). Ferguson recommended to observe in Wardhus (= Vardö, Norway) and in the Salomon islands (Santa Cruz island). Actually, the Tahiti island (which was discovered in 1767) will permit to have a greater parallax.

The schematic of Ferguson [[Ph.tr.-53

p.30-et schémas]] should be compared with the

ones published for the 1761 transit (A

plain Method...) [[ 1605-029 ]].

He took into account the results from the 1761 transit and

assumes here a solar parallax value of 8.5" (instead of 10.5" in

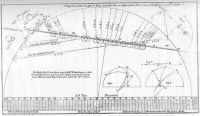

his 1760 book). Hornsby 1766, Ph.tr. 55, p. 326-344 [[ Ph.tr.-55 p.326-344 ]] Thomas Hornsby (1733-1810), professor in Oxford, calculated the 1769 transit predictions. He assumed a solar parallax value of 8.7" and predicted, because of the parallax effect, an increase of the transit duration of 11 min 40 s in Tornea (currently : Finland) or of 11 min 19 s in Wardhus (Vardö, northern Norway). In reality, the duration was shortened by 12 min 53 s at Tornea (p. 334), which corresponds to a maximum difference of more than 24 minutes in 1769 (Halley predicted only 17 minutes in 1761, with an assumed parallax value of 12.5"). This motivated the preparation of an expedition to the southern seas. Less than one year and a half after the publication of this report, the English Samuel Wallis discovered Tahiti Island in June 1767... Pingré 1767, Report on the choice... Venus 1769 [[1628-1 (001à095) ]] Pingré recommended to go and observe the 1769 transit in the southern Pacific Ocean and in the tropical part of America (in particular at Saint-Luke’s Cape in California were Chappe will be observing). Himself went to Saint-Doming (Antilles). [1628(1)] Pingré Alexandre, Mémoire sur le choix et l’état des lieux où le passage de Vénus du 3 juin 1769 pourra être observé avec le plus d’avantage ; et principalement sur la position géographique des isles de la mer du Sud, (Report on the choice and the status of the sites were the June 3, 1769 Venus transit can be observed with the best profit) Paris, 1767, in 4°, (92 p). Observations of 1769Various authors, HMARS 1769 This selection of the Royal Science Academy reports of the year 1769 encompasses a great number of observations of the transit of June 3, 1769. The most noteworthy are : - Le Monnier that calculated the solar parallax value should be comprised between 7.5" and 10". He obtained this result from the combination of observations from France, Finland (Cajanebourg = Kajaani), and Saint-Doming island (Antilles). [[ HMARS-1769 p.498-504 ]] - Pingré observed in Saint-Doming ; the time of the 1st contact was determined with a precision of 4 s (according to the four observers), but later the weather became cloudy, compromising the observations before the middle of the transit. [[ HMARS-1769 p.513-528 ]] - the Duke of Chaulnes was in Paris. In spite of the bad weather, he observed the 1st internal contact less than 20 minutes before sunset. "l'affluence des Spectateurs qui troubloient beaucoup les observations par le bruit & le mouvement continuel." “the crowd of spectators was very annoying for the observations because of the permanent movements and noise” [[ HMARS-1769 p.529-530 ]] - de Fouchy was at the Physics chamber of the king in Passy (Paris) ; the rain, the noise and confusion did not permit him to perform a good observation. [[ HMARS-1769 p.531-538 ]] - Lalande indicated that in Brest there was a parallax difference of 2.4 s between Brest and Paris. [[ HMARS-1769 p.546-548 ]] G. de Fouchy 1770, HMARS 1769, p. 163-172 (History part) [[ HMARS-1769 p.163-172 ]] Funeral panegyric of Chappe d'Auteroche (1728-1769) told by the Science Academy secretary Grandjean de Fouchy, more than one year after his death (August 1, 1769) in November 1770. Chappe died of "une maladie épidémique dangereuse" (a dangerous epidemic disease) in California. After the Venus transit observation on June 3, the whole team stayed there to observe the total eclipse of Moon (night from June 18 to 19) in order to precisely determine the longitude of the observing site. Almost all the team members subsequently died of the epidemic. The French mission in southern California (currently Mexico) performed excellent observations of the Venus transit of June 3, 1769 under the supervision of Chappe d'Auteroche. Unfortunately, most of the team members died a few weeks later of a violent epidemic. Chappe 1772, Journey to California [[ 20140 (0001à0184) ]] This traveler story was written by Cassini iv in 1772 from notes of Jean Chappe d'Auteroche, who died on August 1st, 1769 in California. The second part (p. 69) [[0079 ]] is entirely focused on the transit of Venus dated to June 3, 1770 (sic). Chappe describes the instruments used, the determination of the geographical coordinates and the observations of the transit. The end of the book is a summary about the solar parallax determination, written by Cassini iv. He provides the observations tables of 1761 and 1769 (p. 157 to 159) and concludes a value of 8.5" (p. 168) [[0180 ]] . [20140] Chappe d'Auteroche Jean, Voyage en Californie pour l’observation du passage de Vénus sur le disque du Soleil, le 3 juin 1769 (Journey to California for the Venus transit on the Sun’s disc observation) ; contains observations of the phenomenon and the historical description of the road taken by the author through Mexico, Paris, 1772. French text (172 p). Various authors 1769, Ph.tr. 59, p. 170-445 Observations from the English missions and various letters from members of the Royal Society are archived in the issue 59 of Philosophical transactions (1769). Nevil Maskelyne (1732-1811) was Royal Astronomer in Greenwich. Times are generally indicated in local time (starting at noon). In London, only the beginning of the transit was observable, 5° above horizon, half an hour before sunset. We recommend the following observations : - John Horsfall, at Middle-Temple Hall (London) [[ Ph.tr.-59 p.170-171 ]], - Thomas Hornsby (1733-1810), at Oxford [[ Ph.tr.-59 p.172-182 ]], - Samuel Horsley (1733-1806) at Oxford, with a schematic of the black drop phenomenon p. 184 bis ("a kind of ligament") [[ Ph.tr.-59 p.183-188 ]], - John Bevis (1695-1771), at Kew (10 km west London), noticed the presence of a tiny "trail" between Venus and the edge of the Sun’s disc [[ Ph.tr.-59 p.189-191 ]], - William Hirst, at Inner-Temple (London), describes various phenomena he observed in India in 1761 : a "protuberance" when the contact occurred (p. 229), an atmosphere around Venus (p. 232) ; he confirmed the lack of satellites of Venus. [[ Ph.tr.-59 p.228-235 ]], - Mr Ludlam at Norton, near Leicester (times are reported p. 239) ; the Sun’s elevation was determined with the use of a Hadley quadrant which indicates twice the elevation [[ Ph.tr.-59 p.236-240 ]], - Thomas Wright at the “île-aux-Coudres”island (90 km from Quebec, along the Saint-Laurent river) noticed that Venus seemed to be linked to the Sun’s disc by a "thread" [[ Ph.tr.-59 p.273-280 ]], - Andreas Mayer at Gryfice (near Szczecin, in Poland, where only the external contact was observable) ; the schematic (p. 285) shows the beginning of the entry of Venus on the Sun’s disc, very low on the horizon, as seen through a lens telescope (upside-down image) [[ Ph.tr.-59 p.284-285 ]], - David Rittenhouse (1732-1796) at Norristown (near Philadelphia). Instants are given p. 318-320 ; the 2nd internal contact occurred after sunset ; p. 320 shows observations of Jupiter satellites (which are used to determine the observing site longitude), as well as the conclusion on problems due to errors in the satellites tables ; p. 321, Rittenhouse describes a scaled schematic of the transit prediction (assuming a solar parallax value of 8.65") ; the instant of the geocentric minimum is correct by less than 30s (p. 324) [[ Ph.tr.-59 p.289-326 ]]. - Jardine in Gibraltar, with his observations of the Jupiter satellites and of Antares (the heart of the Scorpion) used for the determination of the geographical coordinates (the elevations indicated are twice the real values, because he used a Hadley quadrant to measure them) [[ Ph.tr.-59 p.347-348 ]], - in France, by various French astronomers [[ Ph.tr.-59 p.374-377 ]], - Francis Wollaston (1731-1815) at East Dercham (25 km west Norwich) ; a cloudy weather masked the internal contact that occurred just above the horizon ; the figures presented p. 408 are related to the partial solar eclipse of June 4 ; Wollaston drew the observed positions of Venus with respect to the Sun’s disc (top schematic, non reversed equatorial coordinates) [[ Ph.tr.-59 p.407-413 ]], - Owen Biddle and Joel Bayley at Lewestown (Lewes, 130 km south Philadelphia, near Cape Henlope, Delaware) [[ Ph.tr.-59 p.414-421 ]], - Daniel Harris at the Windsor castle (40 km west Greenwich) ; in spite of the strong wind, he observed a threat of light at the end of the internal contact (p. 426) [[ Ph.tr.-59 p.422-431 ]]. Rittenhouse (portrait), print [[ Rittenhouse\1davidrit ]] David Rittenhouse (1732-1796) observing in Norristown near Philadelphia. Rittenhouse (observatory), print [[ Rittenhouse\4ritobserv ]] Refuge constructed by Rittenhouse. Scaled schematic of the 1769 transit, calculated by David Rittenhouse for the Norristown observation. A description is archived in the Philosophical Transactions (cf. Ph. tr. 59 (1769), p. 321-325) [[ Ph.tr.-59 p.289-326 ]]. The mission of CookCook 1771, Ph.tr. 61, p. 397-421 [[Ph.tr.-61 p.397-421]] In June 1767, the English Samuel Wallis (1728-1795) discovered numerous islands in the Pacific Ocean, among which Otaheite (= Tahiti) he named “King George’s island” (George III). The French Louis-Antoine de Bougainville (1729-1811) went there in April 1768 and named the island "New Cythère". In the process of expanding their colonies in the southern hemisphere, the English estimated that this island was an interesting observing site for the 1769 transit. The Admiralty and the Royal Society have therefore sent a mission there. The astronomer Charles Green (1735- died in the ocean in 1771) and James Cook (1728-1779) installed a small “observatory” in the settlement called Fort-Venus (nowadays called Point Venus). By independent calculations, Green and Cook both determined the duration between the two internal contacts (about 5.5 hours) with a precision smaller than 20s (p. 410). Unfortunately, the “black drop” effect corrupted the measurements of the contacts instants. Daniel Solander (1736-1782), p. 412, was the assistant of the naturalist Joseph Banks (1743-1820). Different measurements of the Venus diameter lead to a value of 56.4" (p. 418). Measurements of the inclination of the dipping needle was performed, (p. 419) as well as some tidal measurements (p. 420) with their daily cycles (the period of which is 24 hours) instead of the semi-daily cycle (close to 12 hours) as in the northern Atlantic Ocean or in the English Channel. Schematic

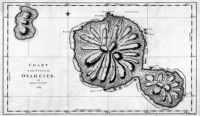

of the black drop effect, print Schematic from the Philosophical transactions n°61 (1771) p. 410 bis, showing the black drop effect as observed by Cook (top) and by the astronomer Charles Green (bottom). Portrait of James Cook (1728-1779), English explorer of the “southern seas”, in quest for Australia. Banks, portrait [[ Banks ]] Joseph Banks (1743-1820) is the (young) naturalist of the expedition. His assistant Daniel Solander (1736-1782), a student of Linné, performed measurements of the Venus transit with Charles Green and James Cook. Endeavour ship, print [[ Endeavour cook21 ]] The ship of the expedition of Cook, (the Endeavour) a three-master, 29 m long, where 90 people can stay. It left Plymouth at the end of August 1768, and came back three years later in Dover in July, 1771. In between, 34 people died (most of them during the trip) from a dysentery epidemic that occurred in January 1771 (among them, the astronomer Charles Green). James Cook drew the map of Otaheite island (= Tahiti, or King George’s island) 60 km long, and of the small island Moorea. Cook observed the Venus transit at the northern point of Tahiti, called "Point-Venus" in the Matavia (Mataval) Bay. The longitude of Point-Venus is correct (149° 30'), but it is not the case for the other longitudes. The latitudes indicated on the map are correct. Matavia Bay, print [[ Endeavour project\Matavia Bay 2-04c ]] The map shows the surroundings of Point-Venus. The current town of Papeete is located 10 km south west of Point-Venus. Fort-Venus, print [[ Fort Venus ]] The over-protected site from which the transit of 1769 was observed (drawing from Sydney Parkinson, member of the expedition). Point Venus, painting [[ Cook-Point-Venus-61601]] View of Matavia Bay. Point-Venus cape, painting [[ Cook-Point-Venus-61609 ]] Viw of the cape, north of the Tahiti island, where was installed Fort-Venus. 1769 observations analysisLalande 1771, manuscripts [[ C-5-29 (001à021) ]] Hand-written calculations from Lalande, performed just before (May 31st), and just after the transit, taking into account the observations performed from Paris (Lalande was personally in Brest) : - p. 300 [[ 004 ]] : Lalande describes his geometric method to calculate the parallax effect. From a given observing site (as Paris for instance), the internal contact is observed in point V, while at the very same instant a geocentric observer see Venus in N : the parallax effect is represented by the difference NV. Lalande calculated that the transit should occur 7min 27s earlier in Paris (p. 301) [[ 005 ]]. In reality she was only of 7min 11s. This mismatch comes from the solar parallax value (9") assumed by Lalande. - p. 311 [[ 008 ]] : after the Paris observation, he calculated the geocentric conjunction instant in order to improve the Venus tables (position of the orbital node). - p. 370 [[ 012 ]] : calculations performed for a Science Academy report. - p. 373 [[ 015 ]] : calculation of Venus density ! Venus actually has a density very close to the Earth one (5.2). Almost all numbers presented in this page are decimal logarithms. - p. 429 [[ 016 ]] : later, end of 1770, Lalande changed his assumption on the parallax value (9" then 8.80" and next 8.67"). On January 21, 1771, he calculated using a parallax value of 8.80”, that this effect should have been of 7min 11s. This result is amazingly correct ! (p. 435) [[ 021 ]].

Hornsby 1771, Ph.tr. 61, p. 574-579 [[ Ph.tr.-61 p.574-579 ]] Thomas Hornsby (1733-1810), professor at Oxford, analyzed the observations of the 1769 transit : - in Wardhus (= Vardö northern Norway), by Hell, - at Kola (Northern Russia) by Rumovsky, - at Hudson Bay (Canada) by Wales and Dymond, - in southern California (currently Mexico) by Chappe, - at the King George’s island (= Tahiti), by Green, Cook and Solander. Hornsby assumed a parallax value of 8.7" (p. 576) and found 8.78" (p. 579). He added a table containing the absolute distances of the planets to the Sun, with 6 significant digits… Lalande 1771, HMARS 1771 p. 49-50 [[ HMARS table 1771-1780 p. 49-50 ]] (See the article “Astronomy” at the bottom of the table of contents p. 49). The complete article HMARS 1771 p. 776-799 that corresponds to this pages is not available. Lalande analyzed observations from Tahiti, China and Russia. Assuming a solar parallax value of 8.5", he found 8.62". Pingré 1772, HMARS 1772 p. 398-420 [[ HMARS-1772 p.398-420 ]] Alexandre Pingré (1711-1796) observed the 1761 transit from the Rodriguez Island (in the Indian Ocean), and the 1769 transit from Saint-Doming Island (Antilles, where he observed only the first half due to a cloudy weather). He deals here with 5 complete episodes : - in Tahiti, with Green, Cook and Solander, - in Saint-Joseph, California (nowadays called San-José del Cabo, Mexico) by Chappe, Doz and de Medina, - at the Prince of Wales Fort in Hudson Bay (Canada) by Wales and Dymond, - at Wardhus (= Vardö northern Norway), by Hell, Sajnovicz and Borgrewing, - at Kola (Northern Russia) by Rumowsky, where the first contact was perceived rather than really observed. He adds the observation from Cajanebourg (= Kajaani, in Finland) by Planman although some clouds slightly corrupted the observations of the second contact. Assuming a parallax value of 8.5" (p. 408), he found a value of 8.8" (p. 419) which he estimated to be very approximative. J.-A. Euler 1772, Ph.tr. 62, p. 69-76 [[ Ph.tr.-62 p.69-76 ]] Johann-Albrecht Euler (1734-1800) is the eldest son of Leonhard Euler (1707-1783). As his father, he was a member of the Science Academy of Saint-Petersburg. From observations of 1769, he estimated that the solar parallax value is comprised between 9" and 10". Newcomb 1891, Astronomical Papers [[ 2929 (0001à0137) ]] The American Simon Newcomb (1835-1909) realised a huge work around 1890. He reconsidered all observations from the transits of 1761 and 1769, using better longitudes determinations. He extensively studied the instruments used and estimated the corresponding uncertainties. Observations of 1769 are described p. 296 to 329. The observing sites coordinates are given p. 343 to 345. Newcomb used a semi-diameter value of the Sun of 959.78" (at 1 astronomical unit) and 8.46" for the one of Venus (at 1 AU) (p. 348) [[ 0080 ]] . Through an adapted mathematical process, he found a value of the solar parallax of 8.79" +/- 0.05" (p. 402) [[ 0134 ]] which corresponds to a precision smaller than 0.6 %. [2929] Newcomb Simon, Astronomical Papers prepared for the use of the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac, vol II, , 1891, Part V., Discussion about Venus transit observations in 1761 and 1769. English text (136 p). About the different observations of 1769 : [1524(1)] [Anonymous author] Collectio omnium observationnum quae occasione transitus Veneris per Solem, Petropoli, 1770. Latin text (622 p). About the transit of 1639 observed by Horrocks and Crabtree, and historic of the transits of 1761 and 1769 : [1478, tome 2] et [1478, tome 4] Montucla, J.-F. , Histoire des mathématiques… (History of mathematics) (includes some elements about the Venus transits), Paris (1799). 4 vol. French texts (extracts). |